RESEARCH PROCESS

I have always been deeply fascinated by the mysteries of prehistory, believing that understanding the past can illuminate the origins of humanity and provide insights into why we exist. This curiosity has driven my exploration of archaeology, mythology, and ancient religions—fields that address fundamental questions about existence and the human condition. These themes form the foundation of my artistic practice, alongside inspiration drawn from philosophy, nature, and contemporary art. By engaging with these ideas, I strive to create works that examine the fragility of life, the impermanence of existence, and humanity’s enduring connection to the natural world.

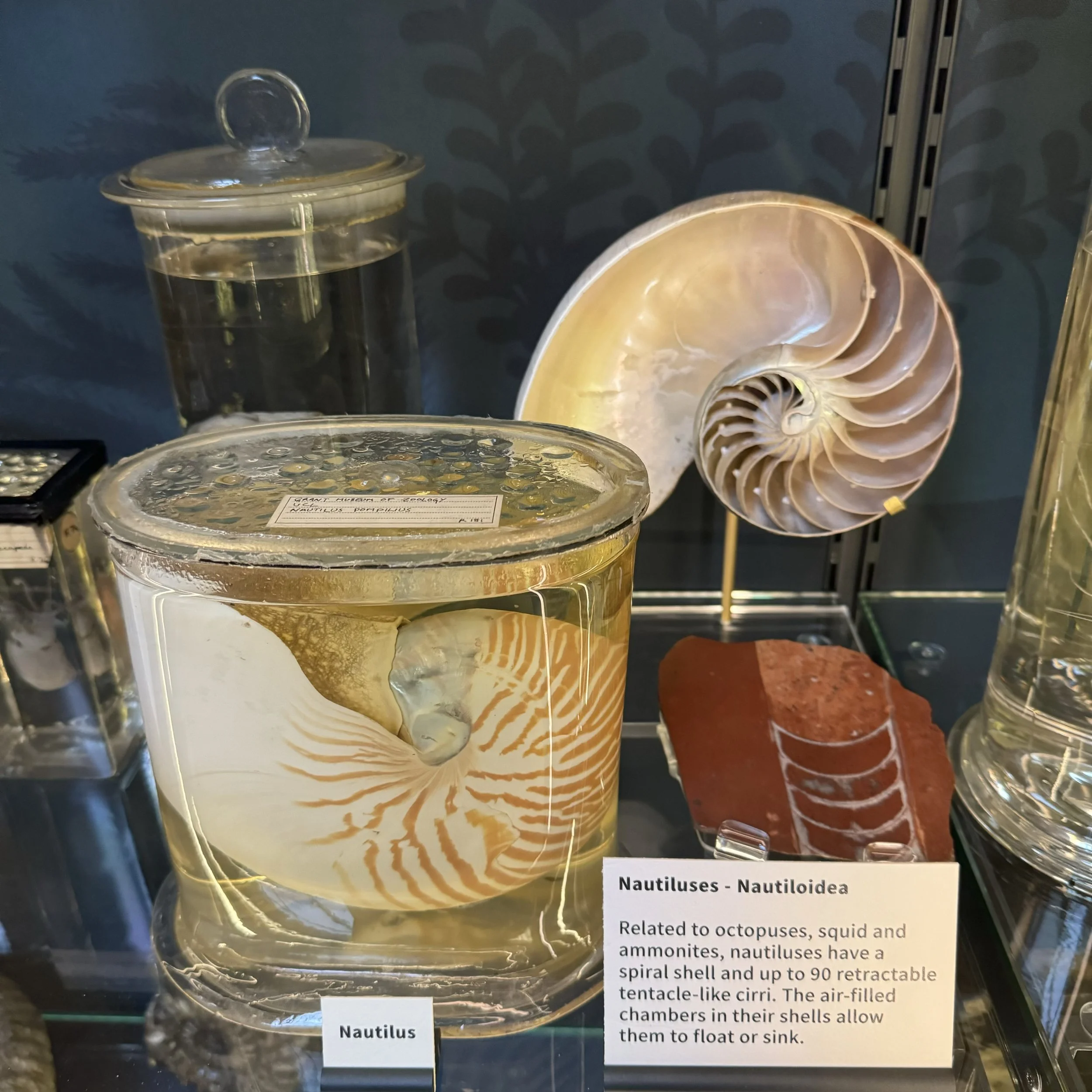

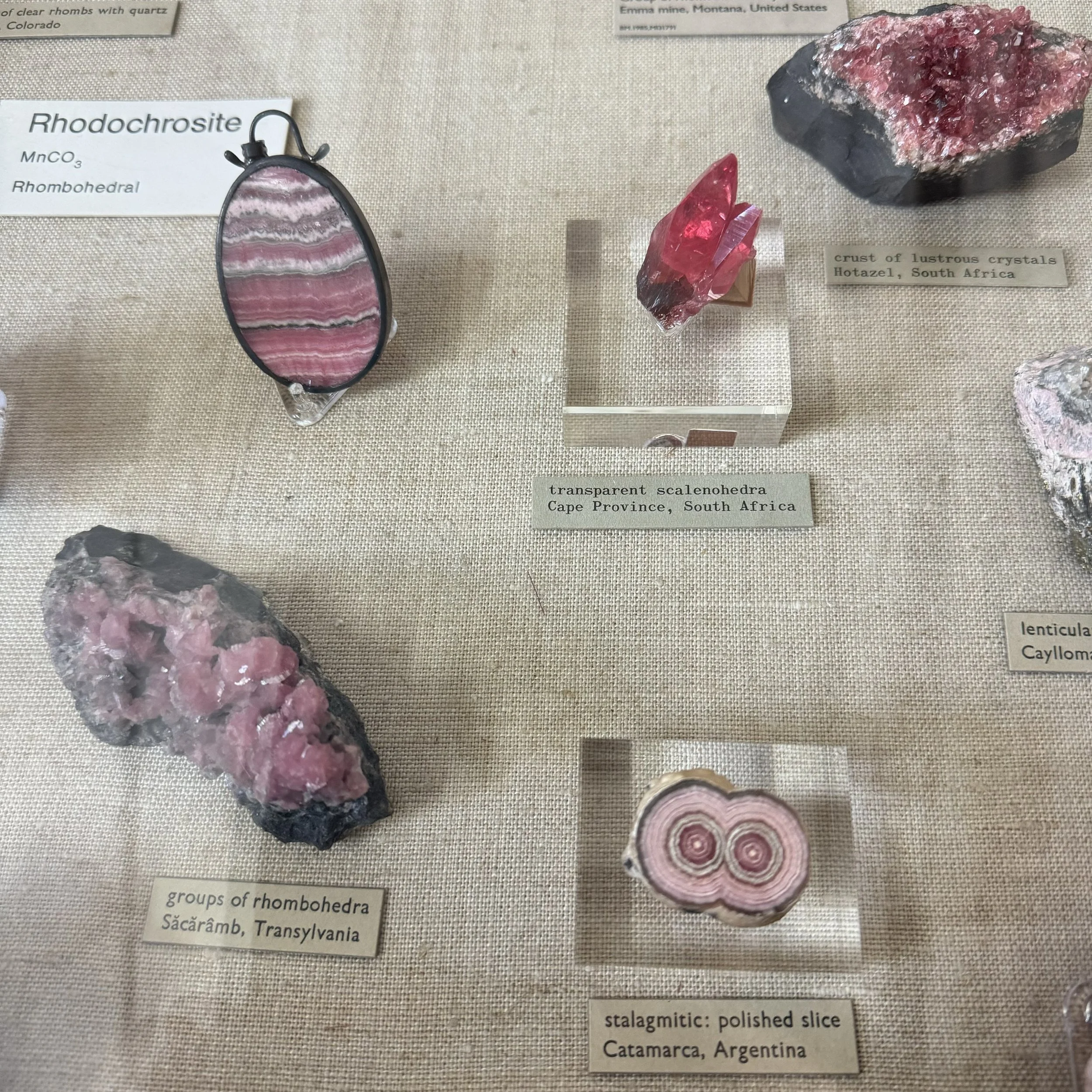

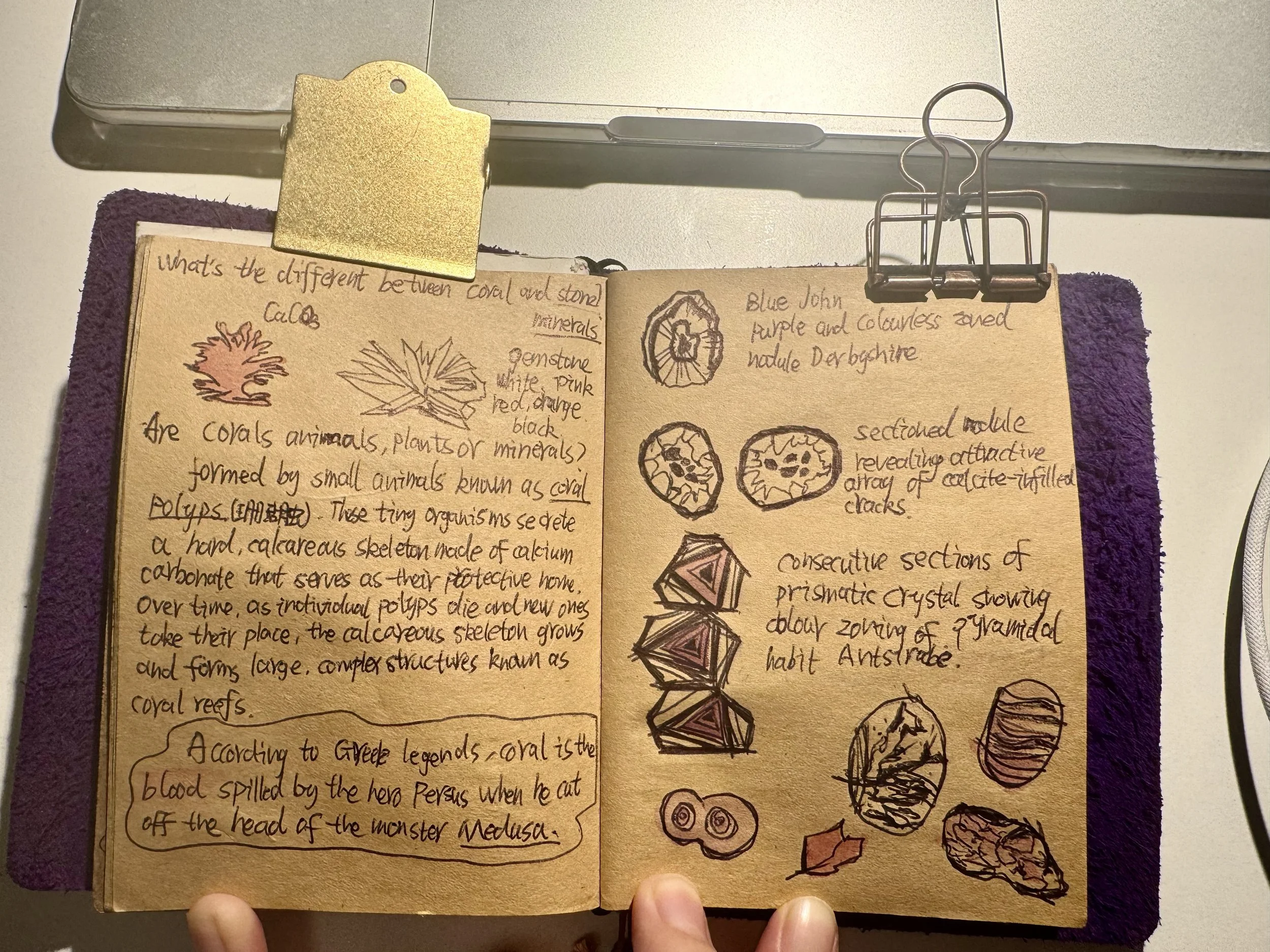

When I first arrived in London, the city’s wealth of museums and historical landmarks expanded my understanding of art and deepened my appreciation for the interplay between life and death. Museums like the Natural History Museum and the Museum of Zoology captivated me with their vast collections of bones, skulls, and preserved specimens. Each object seemed to hold a unique story, representing a fragment of life that once existed. These artifacts sparked my curiosity about the lives these creatures led and their connection to the natural world. Bones, in particular, became central to my practice as they symbolize the boundary between life and death. They are remnants of life, yet they persist long after death, embodying transformation, memory, and continuity.

Digital print

Ceramic fossil test

Image transfer test out

Using news paper to absorb extra ink

Ceramic bones and skeleton test

Digging For Britain

Mono print again on digital print

Casting for wax sculpture

Mono print drawing with white sprite

The Great Chain of Being, Richard James, 2023

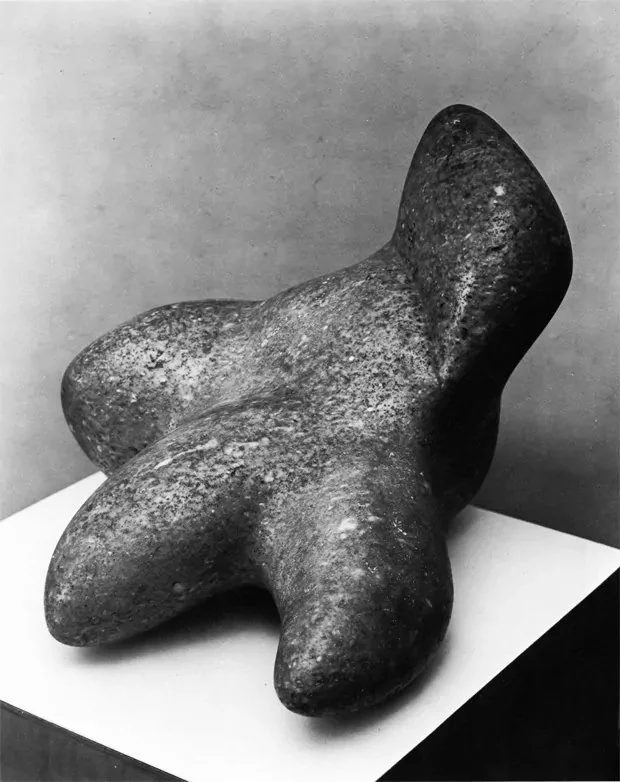

Jean Arp

Nadine Baldow

Sam Hodge

OTHER REFERENCE

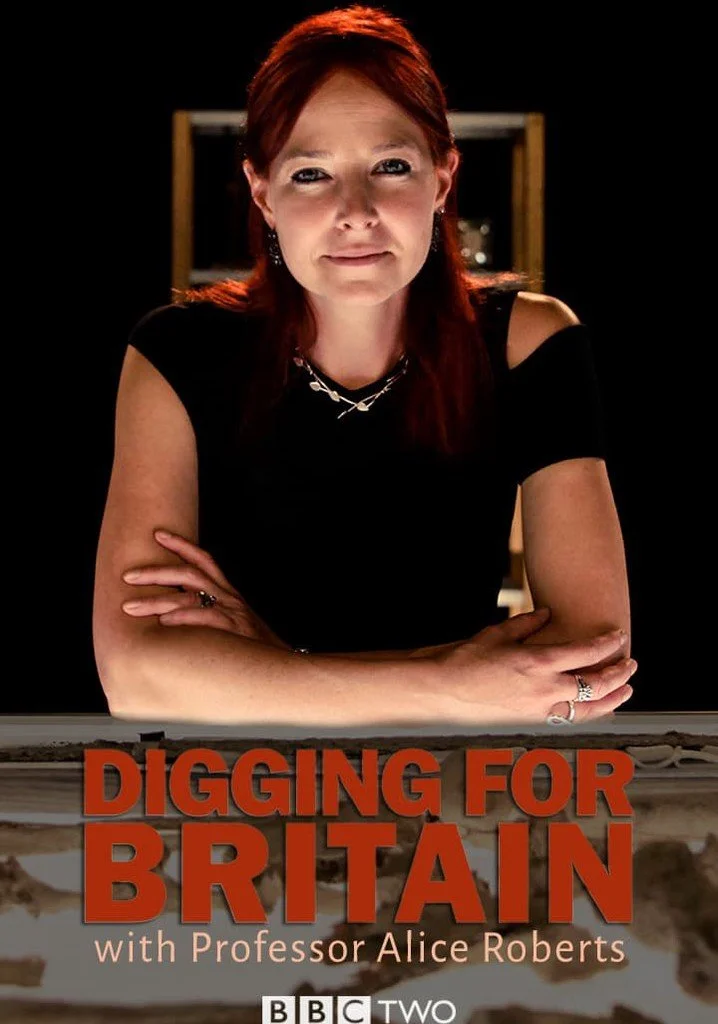

In addition to artistic influences, documentaries have significantly shaped my practice. I am particularly inspired by Digging for Britain, which highlights archaeological discoveries and their relevance to understanding prehistory. This documentary introduced me to sites like Lesnes Abbey Wood Fossil Park, where fossils of marine creatures and early mammals provide a tangible connection to life millions of years ago. Visiting this site and collecting materials such as soil and stones has enriched my practice, allowing me to incorporate elements of archaeology into my exploration of life and death. These materials serve as physical links to the past, grounding my work in the deep history of the Earth.

Lesnes Abbey

Philosophy provides another critical foundation for my work, offering frameworks for understanding the themes I explore. Martin Heidegger’s concept of "Dasein", encapsulated in the phrase “being-there,” deeply influences my approach to art. Life, as I see it, is defined by transformation and impermanence—a theme I convey through my use of materials like wax, which melts and reforms, symbolizing life’s evolving stages. Carl Jung’s theory of the collective unconscious also resonates strongly with me. Jung’s idea that the deepest layers of the human psyche are shared across cultures and time explains why ancient symbols and petroglyphs evoke universal feelings of connection and awe. This realization inspires me to create symbolic compositions using natural materials, aiming to evoke the primal instincts and collective memories that unite humanity, "Object-Orientd Ontology" by Graham Harman also gives me inspirations on my series Object.

One of the recurring themes in my work is the idea of creating symbols and narratives that transcend language. By arranging objects like stones, bones, and soil in specific compositions, I seek to evoke the spirit of ancient hunter-gatherer societies, where storytelling and meaning were conveyed through objects and symbols rather than words. This approach reflects my belief that art can serve as a universal language, connecting viewers to the shared experiences and emotions of humanity.

In my practice, I also aim to balance reverence for nature with an exploration of humanity’s impact on the environment. My use of natural materials highlights the interconnection between human and non-human life, while also prompting reflection on the fragility of ecosystems. By incorporating materials like soil and bones collected from my surroundings, I emphasize the continuity between life and death and the cycles that sustain existence.

Ultimately, my work is a meditation on life’s fragility, transformation, and interconnectedness. By drawing on natural materials, ancient philosophies, and contemporary influences, I seek to create artworks that provoke reflection and invite viewers to consider their own connections to nature, history, and the enduring mysteries of existence. Through my practice, I aim to bridge the past and present, exploring the universal themes that define humanity and its relationship with the natural world.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung (1819) Schopenhauer

Romance in the age of Uncertainty (2003) Damien Hirst

The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, (Collected Works of C. G. Jung), Routledge; 2nd edition (6 Jun.1991)

Being and Time, Martin Heidegger, Harper Perennial, 2018

Object- Oriented Ontology, Graham Harman, Penguin Books,2018-03-01

Parker, C. and Schlieker, A. (2022) Cornelia Parker. London, England: Tate Publishing.

Stewart, S. (1993) On longing: narratives of the miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir, the collection. Durham, N.C., London: Duke University Press

Bennet, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Bogost, I. (2012) Alien Phenomenology or What it’s Like to be a Thing (Posthumanities). Minnesota: Minnesota University Press.

Groys, B. (2017) Curating in the Post-Internet Age, e-flux journal #94 October

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/94/219462/curating-in-the-post-internet-age/

Hawkins, H and Olsen, D, eds. (2003) The Phantom Museum and Henry Wellcome’s Collection of Medical Curiosities, London: Profile Books

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Reel.

Leslie, E. (2005) Synthetic Worlds: Nature, Art and the Chemical Industry. London: Reaktion Books.

Lilley, C. (2015) Materiality. London: MIT Press/Whitechapel Gallery.

Lowenhaupt Tsing, Anna (2015) The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Start to draw skeleton photos i took in the Natural History Museum

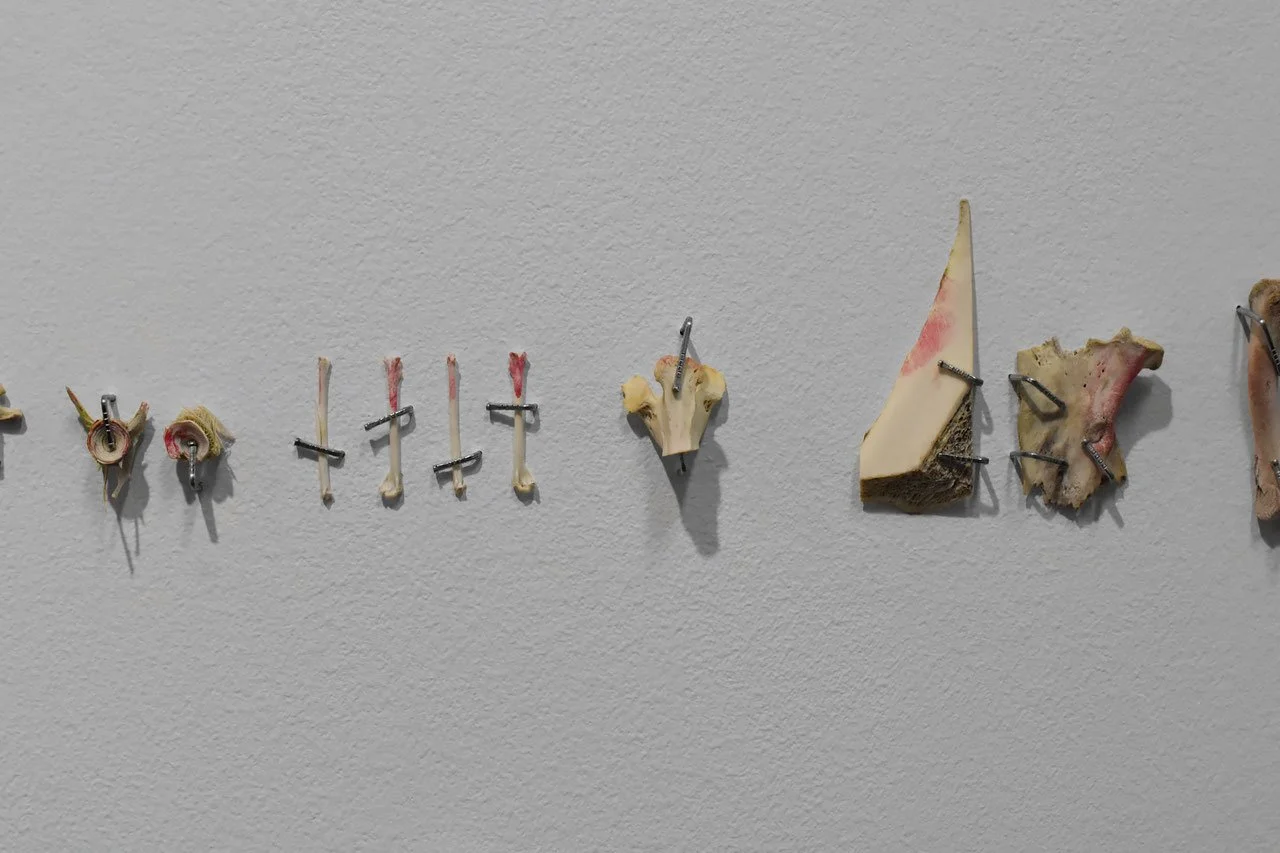

Stones and shells I found while I mudlarking, bones from supermarkets and butchers

When I began studying printmaking, I had no prior experience, so I explored every technique introduced during the induction—monoprinting, relief printing, screen printing, and lithography. However, I found etching particularly captivating because of its rich textures and endless possibilities for variation. This drew me to persist in exploring it further.

As I continued experimenting, I started collecting stones and bones, photographing them in different settings. During the three-day print project, Peter Roberts introduced us to image transfer, which I found especially intriguing. I used this technique to create my Object Series, transferring images onto plywood. The natural wood grain blended seamlessly with my photographs, adding depth and detail that made the images feel more alive.

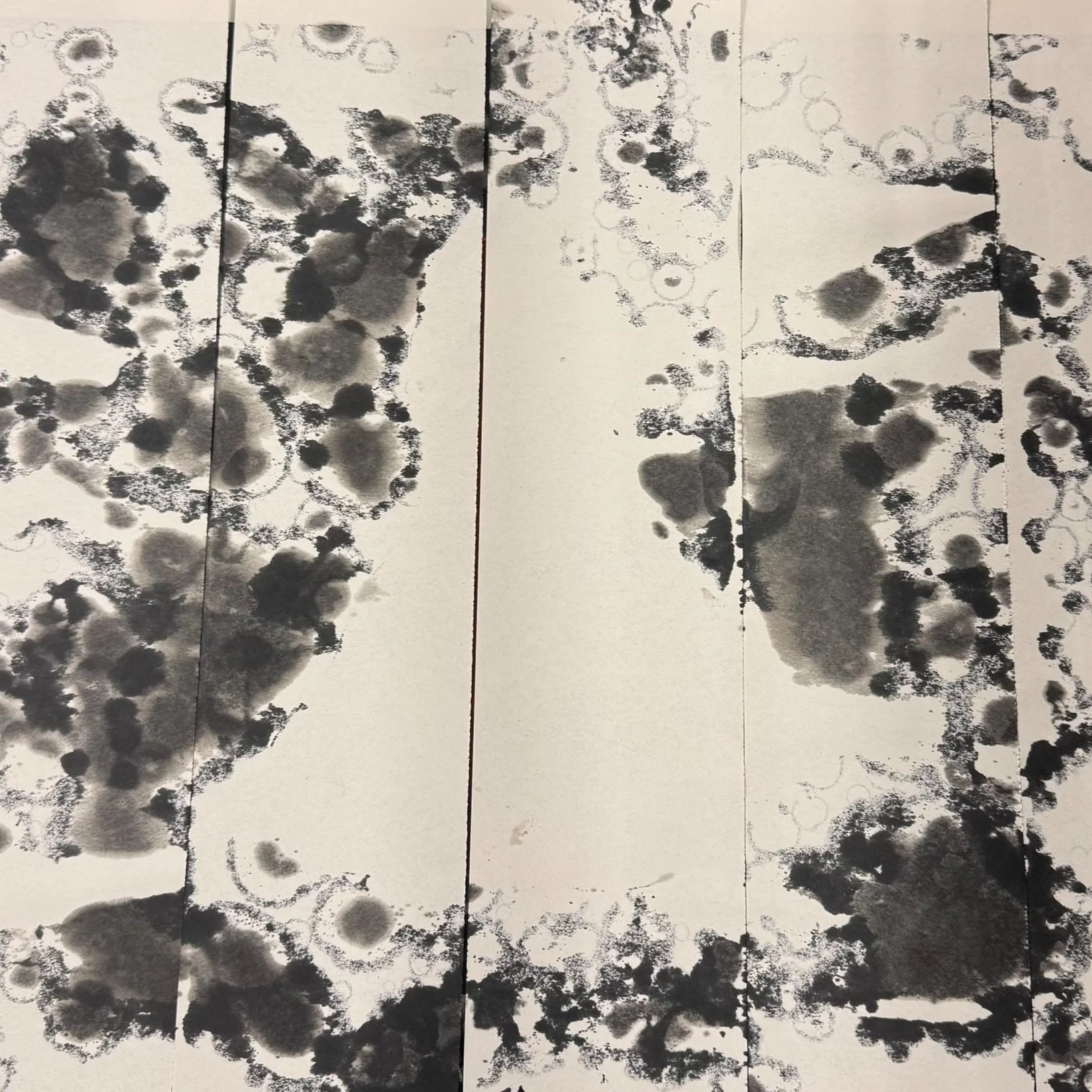

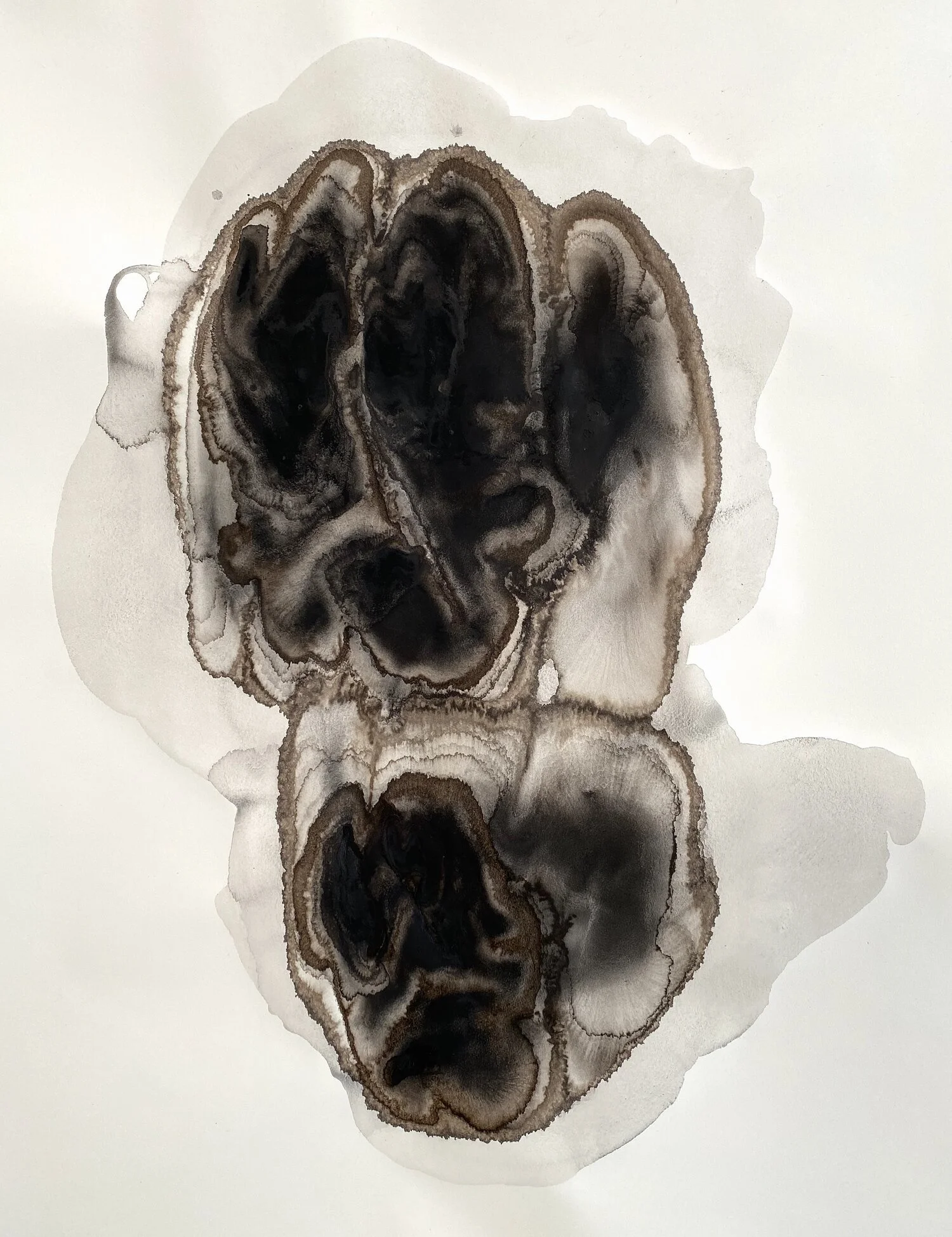

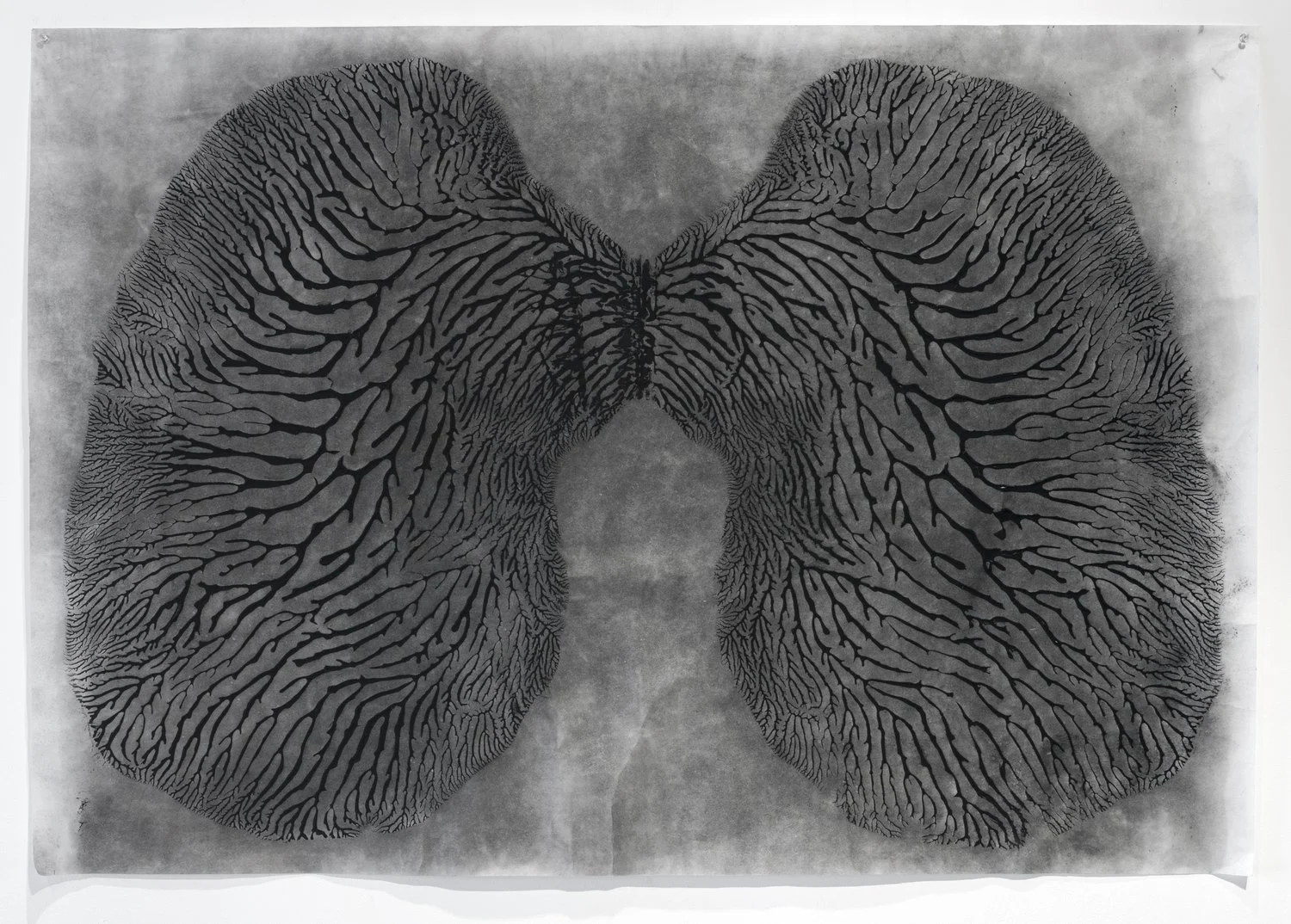

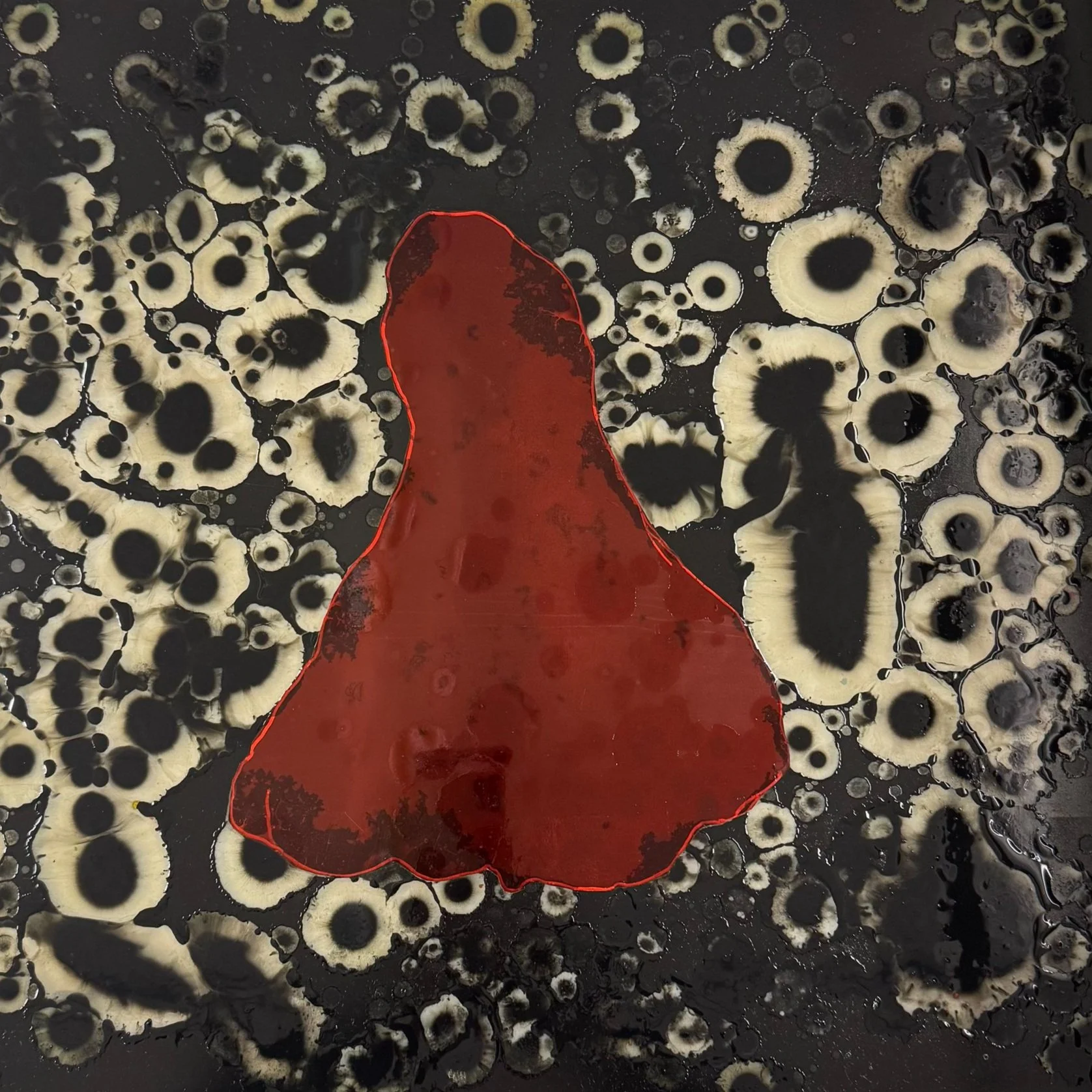

Alongside that, I developed the Existence Series using monoprinting techniques. Fiona taught me how to use white spirit to create organic patterns on a black inked board. The resulting textures resembled microscopic cellular structures, offering a scientific perspective on life itself.

Beyond printmaking, I also wanted to create objects by hand. I initially experimented with ceramics to sculpt skeletons, bones, and fossils, but the results weren’t quite what I envisioned. Instead, I turned to casting and modeling techniques to replicate the shapes of the bones and stones I had collected. Eventually, I created wax sculptures of these forms, drawn to the material’s transformative nature—wax melts, shifts, and changes with heat, much like life itself, which is always in flux and finite. This idea became the foundation of my Life Series.

Mono print use extencols

My artistic influences are varied and deeply rooted in my exploration of the natural world and its materials. Anne Covell’s work, particularly Cult of Relics, resonates strongly with me. Her use of natural objects to create reliquaries elevates these materials, imbuing them with a sense of reverence and challenging what we as humans choose to venerate. This idea aligns with my own belief that natural objects—stones, bones, and soil—carry stories and meanings that transcend their physical form. Similarly, Richard James’s work has had a profound impact on my practice. His exploration of the mysterious and the sublime in everyday remnants inspires me to uncover the hidden narratives within the objects I collect. His use of natural materials to create reliquaries mirrors my own process of collecting and transforming found objects into artworks that reflect on life and death.

ARTIST REFERENCE

Cult of Relics, Anne Covell, 2015

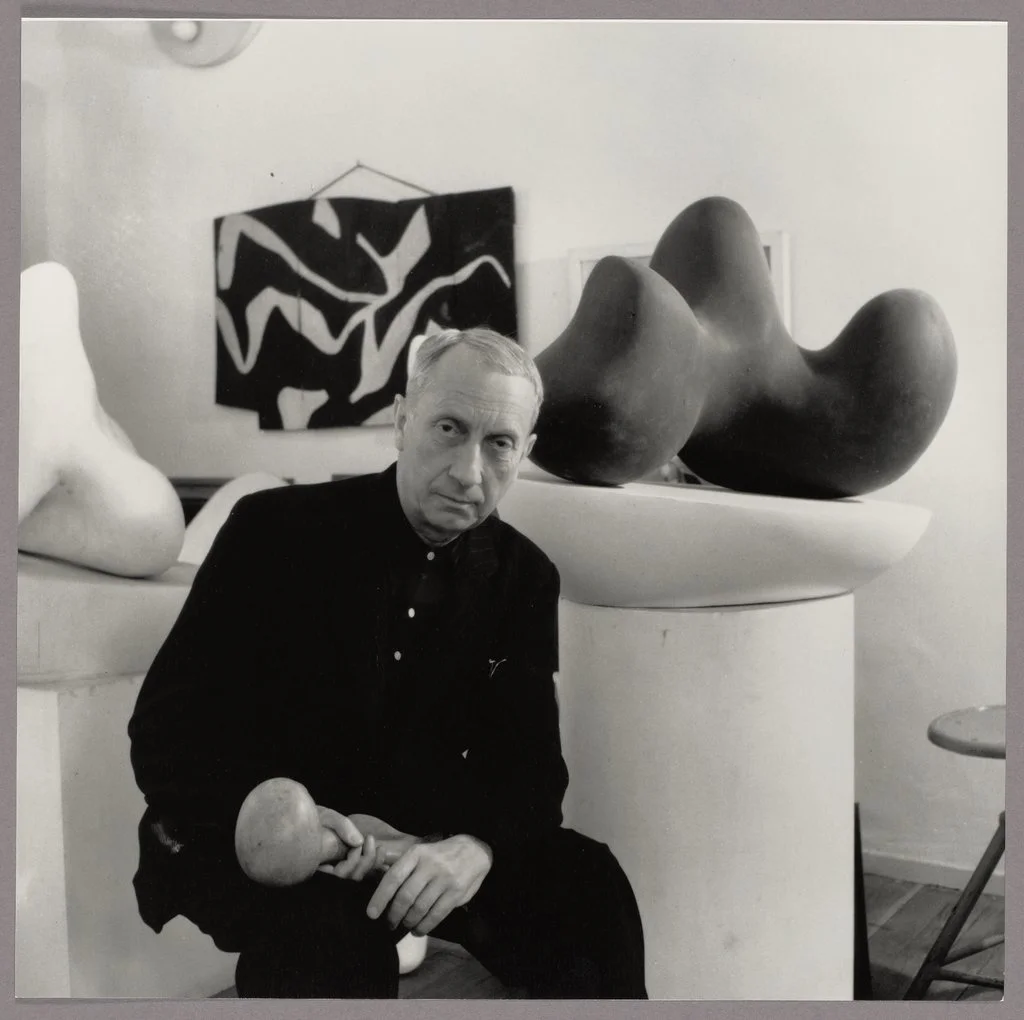

The concept of biomorphism has also become central to my practice. When I first encountered Jean Arp’s work, I recognized the parallels between his abstract forms and my own use of natural materials to evoke organic shapes. Biomorphism, which draws on living forms to create art, provides a framework for exploring the interconnectedness of life and nature. Artists like Nadine Baldow and Sam Hodge have further inspired me with their use of biomorphic forms to address environmental and existential themes. Baldow’s exhibition We Must Be Brave. We Must Be Fragile particularly resonated with me. Her gentle yet profound approach to exploring the impact of urban life on the natural world through objects like bones inspired me to consider the subtle ways materials can convey meaning. Similarly, Hodge’s exploration of humanity’s entanglement with the material world and its instability aligns with my interest in the fragility and transformation of life.